Transition into Industry 4.0

Whilst the implications of a mismanaged hyper-intelligence are concerning, we are currently facing more pressing technology related issues, such as its effect on the global economy and the job market. A huge transformation is happening around us, which could perhaps be perceived as the industrial revolution of our times. The question on many people’s minds is; will robots steal our jobs? The bitter truth is; they have already started doing so.

Due to advancements in artificial intelligence, automation and robotics many professions are left with the prospect of being rendered obsolete. The diversity of applications are quite varied, sophisticated algorithms and automation software are replacing accountants, administrative personnel, office workers and even law professionals. Self-driving vehicles have the potential to disrupt the future of the transport and logistics industries, eliminating the need for human drivers. Manufacturing will be one of the hardest hit sectors, where general purpose robots with learning capabilities, such as Baxter, can replace human workers at factories once they learn how to do their daily jobs. Unlike humans however, software and robots don’t need to rest, eat or face psychological turmoil, making them the perfect workers.

According to Klaus Schwab, Founder and Executive Chairman of the World Economic Forum; this is not where it ends, this is only the beginning. The computer and automation revolution we have been experiencing will be promptly followed by what he calls “the 4th industrial revolution”.

Industry 4.0 represents the possibility of combining cyber-physical systems, the so called Internet of Things (IoT) – physical sensors capturing and storing data in real-time, and the internet of systems – software systems managing various aspects of a business. A perfect harmony between digital, physical and biological actors in business established through interconnected technology.

Imagine a factory where the assembly line is optimized according to market demand in real-time, production output is adjusted, the supply chain and logistics functions are automated thanks to general purpose robots, autonomous vehicles and machine learning algorithms.

This gives you an idea of how Industry 4.0 can change the way we do business. As you can imagine the impact of such sophisticated technology will be drastic on employment levels.

Future of Employment

A 2013 empirical research study conducted by Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael Osborne, of the University of Oxford, claimed that around 47% of the US employment is in the high risk category of losing their jobs due to automation in the next two decades.

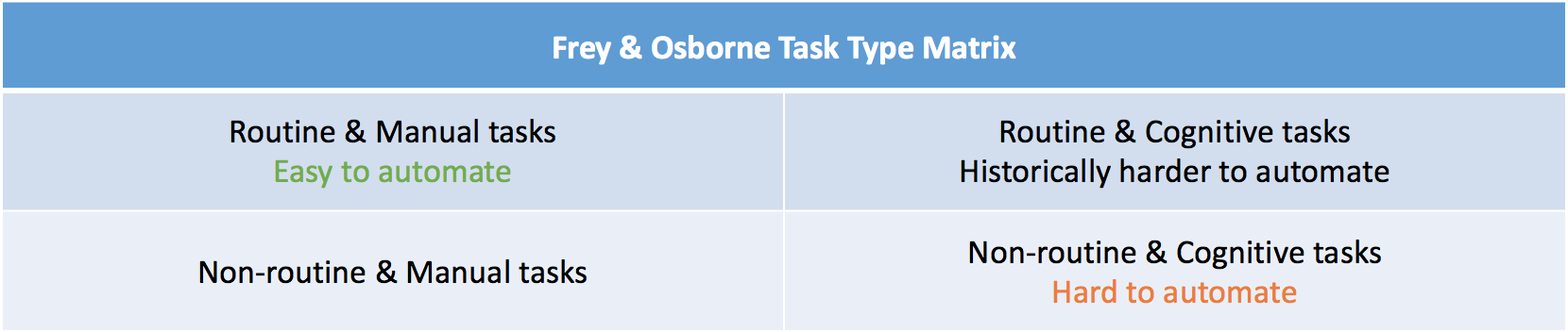

Frey and Osborne conducted their analysis by identifying variety of tasks involved with each profession and classifying them into a 2 by 2 matrix.

Historically, professions involving routine and manual tasks were most likely candidates for automation which is evident from the decline of manufacturing jobs, on the contrary, non-routine and cognitive tasks were less susceptible to automation such as engineering jobs. However, current machine learning algorithms can perform non-routine operations as long as a big dataset is available from which insights can be captured, we are no longer confined to rigid logic structures in software. So, automation of non-routine tasks is slowly becoming a reality as well.

In order to rank which jobs are less likely to be automated, Frey and Osborne highlighted the skills humans possess which are hard to replicate by automation or artificial intelligence.

Ability to examine surroundings and identify items of interest in a cluttered view.

Significant advancements have been made in the field of machine vision enabling computers to effectively identify objects but they still lack the intuition and insight into how identified objects might be (ir)relevant to the task at hand.

Dexterity

Dexterity of the human body, especially our hands allows us to work in cramped situations, an evolutionary trait which solidified mankind’s grip on power. Apart from specialized medical robots which can replicate such levels of dexterity, an economically viable mass-market robot is yet to come.

Creativity

Creative capabilities to come up with unusual and creative ideas to solve problems.

Social Intelligence

Ability to perceive emotions, persuade and negotiate with others.

These are the current bottlenecks to the automation of jobs involving tasks with such characteristics.

As a result, Frey and Osborne argued that workers in transportation and logistics industries along with office and administrative support staff are in the high risk category. Workers in production and construction industries also fall into this category. Sales jobs which seemingly requires a high degree of social intelligence also fall into the high-risk bracket. For example cashiers, counter and rental clerks, and telemarketers do not necessarily require high levels of social intelligence, so further advancements in AI might replace their jobs as well. Furthermore, paralegals and legal assistants are in the high risk category whereas lawyers are in the low risk category.

Occupations involving installation, maintenance and repairing physical devices are in the medium risk category due to the fact that manual handling in various different environments will be hard to automate in near future.

The fields of computing, engineering and science are in the low risk category as they require creative intelligence and also familiarity with different bodies of knowledge. Business, management and finance professionals are also in the low risk category due to highly generalist and social nature of their professions.

Frey and Osborne’s paper illustrates a bleak picture for majority of the workforce, claiming that 47% of jobs are on the line in the next two decades. However, robots and automation replacing human labour doesn’t simply boil down to the level of technological advancements. David Autor, an economist at MIT, states the following argument in his 2013 paper:

The mere fact that a job can be automated does not mean that it will be; relative costs also matter. When Nissan produces cars in Japan, it relies heavily on robots. At plants in India, by contrast, the firm relies more heavily on cheap local labour.

Apart from the economical factors, support of public institutions and society are crucial in adopting new technologies. To better help us understand how society copes with major shifts in technology, we can study the development of previous industrial revolutions and examine how society managed to steer these drastic changes to benefit people from all walks of life.

A gaze into the past, an insight into the future

“The more distant we look into the past, the farther we can see into the future.”- Winston Churchill

In 1589, William Lee, a British inventor, demonstrated his stocking frame knitting machine to Queen Elizabeth I to seek approval for a patent. However, to his bemusement the application was turned down by the queen due to the potential impact of the invention on employment. Afterwards, Lee had to leave the country for good amid pressure from the trade guilds.

Between 1811 and 1816, textile workers in England revolted against Parliament during the so called Luddite Riots. On the surface it appeared workers were revolting due to the fact that a 1511 law prohibiting the usage of a specific machinery in wool production was revoked, however the manifestations can actually be tied to fear of technological change among workers. Protestors were met by stern opposition from the the government. A few years after the Luddite protests, in 1821, British economist David Ricardo described the industrial revolution as the “substitution of machinery for human labour”.

Contrary to the backlash against technological developments, economic variables indicate that the industrial revolution actually brought positive change. It helped to create sufficient jobs to soak up the booming population of the 20th century and where existing jobs in manufacturing were replaced, new jobs were created in other industries such as services. Many studies were conducted on workers’ living standards during the industrial revolution, a 1998 study conducted by economic historian Charles Feinstein, claimed that average working class living standards in Britain increased by 15% between 1770 and 1870.

Current economical trends

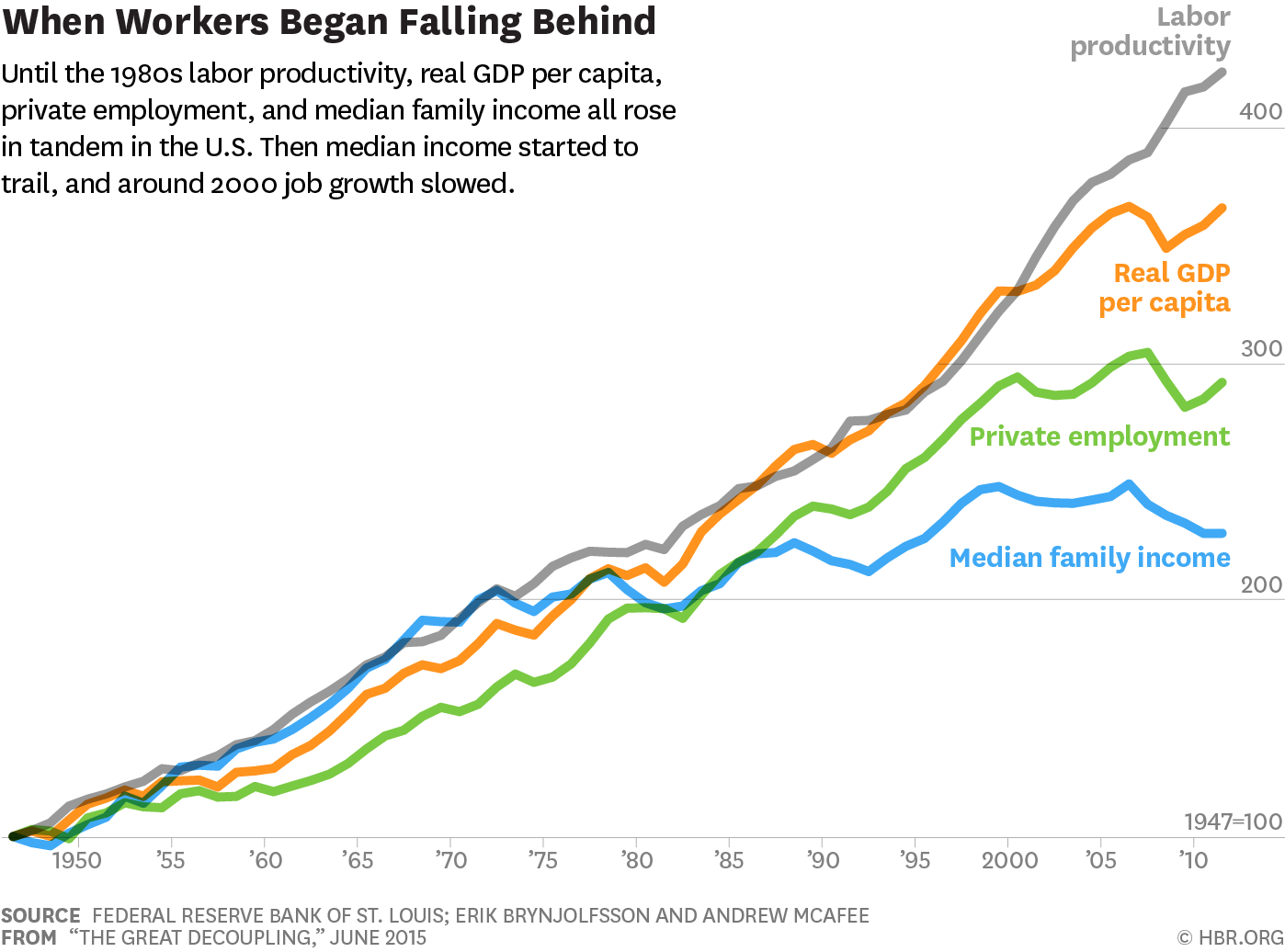

Some economists argue that the advancement of technology we see today is not bringing the same rewards as the previous industrial revolution, Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew Mcafee, academics at MIT Sloan School of Management, believe that technology is destroying jobs faster than it is creating them, contributing to the stagnation of median income and further dividing the inequality gap.

Brynjolfsson and Mcafee base their claims on productivity and employment levels after World War II, two economic indicators which follow parallel trends until the beginning of 2000. As productivity increases, economic activity flourishes creating more jobs. At the beginning of the 2000s, employment levels start to stagnate despite the continued increase in productivity, leading up to what Brynjolfsson and Mcafee call “great decoupling”. Technology is advancing so fast that workers, businesses and institutions can’t keep up. In order to stay relevant in the future, people and institutions need to acquire new skills faster than the pace of technology, it is a race between humans and technology!

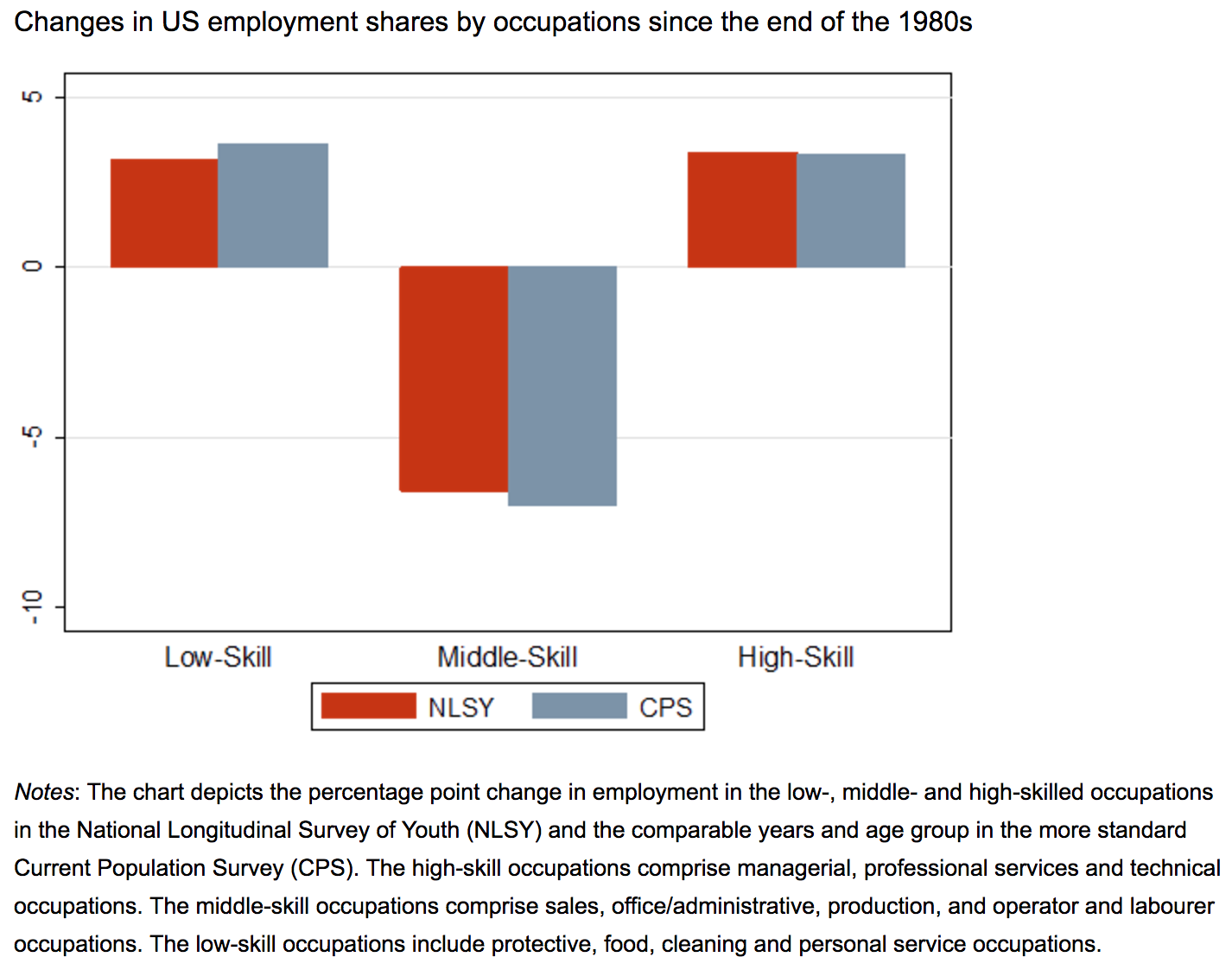

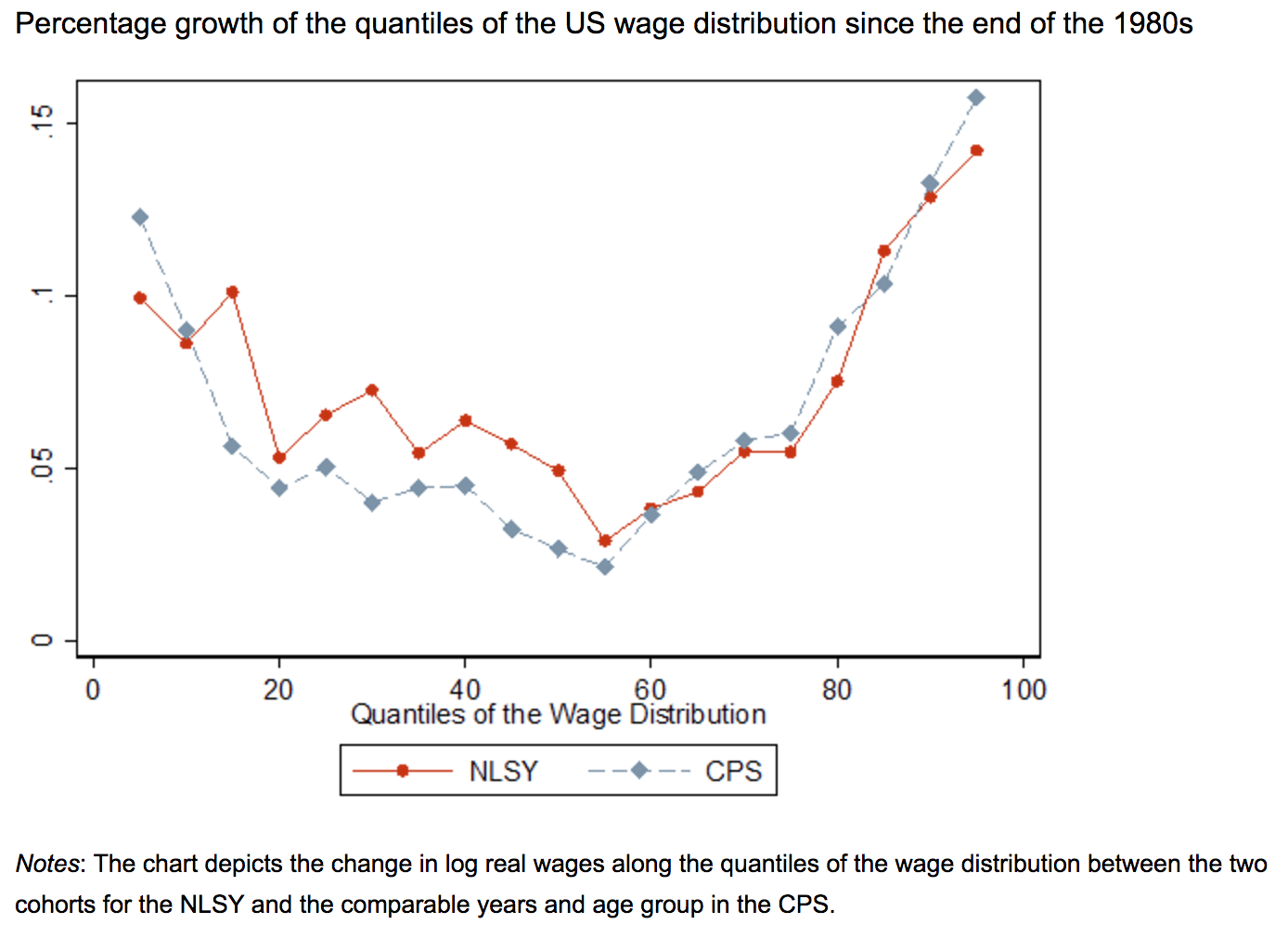

Another interesting economical trend influenced by technology is job polarization. A 2007 research conducted by David Autor of MIT found out that the share of employment in middle-skilled jobs has declined rapidly both in Europe and US since 1980s. Autor attributes this trend to automation of many routine and manual jobs by software or machines. This trend is hollowing out the middle class, resulting in polarization of incomes as well. Percentage of growth in wages of low and high skilled workers has been bigger than middle skilled workers.

Perhaps, the most compelling and a living, breathing example of tectonic shifts outlined by economic indicators above is the de-facto capital of technology, San Francisco. Likes of Google, Apple and Facebook are operating tech shuttles for their employees amidst frequent protests by long time residents of the city. Influx of well paid, young tech workers have driven rent and property prices above the roof, pricing out many San Franciscans. In 2013, homeless has set up a camp known as "the jungle" in the city, just 10 minute drive away from Oracle's campus in San Jose. A real life juxtaposition of how technological advances are affecting the society in completely opposite ways.

Not all hope is lost though, industrial revolutions always begin with greater inequality, followed by social and political reform. If we have managed to steer the change in the right direction before, why should not we able to do it once again? Success of previous industrial revolutions can be attributed to the rise of trade unions, adoption of universal post-secondary education, fiscal reforms and introduction of social safety nets.

In the final part of this series, I'll be discussing the potential education and social reforms.

This is the second of three essays on automation, robotics and artificial intelligence. Second essay focuses on the impact of technological innovation on the job market and economy. Click here to read the first essay about the development and outlook of artificial intelligence field.